|

Powered by WordPress

|

Sunday: February 5, 2012

On his fifty-sixth birthday, Terry Teachout laments that “56 is a thoroughly uninteresting number”. Au contraire: it is quite significant as a birthday, perhaps the most significant birthday of all.

Solon was the first (or one of the first) to write on the ‘Ages of Man’ theme, best known to English-speakers from Jacques’ “All the world’s a stage” monologue in As You Like It, II.7. Where Shakespeare distinguished seven ages with no specific lengths in years, Solon had divided the life of man into ten ‘hebdomads’ or periods of seven years each. I quoted the whole passage (Fragment 27, in M. L. West’s English translation) without comment on my fifty-sixth birthday. The most important part for Terry is lines 13-18:

With seven hebdomads and eight – fourteen more years –

wisdom and eloquence are at their peak,

while in the ninth, though he’s still capable, his tongue

and expertise have lost some of their force.

For the mathematically-impaired, that means that one’s mental peak (or perhaps plateau, given its extent) is from the 42nd to the 56th birthday, and after that it’s all downhill. Welcome to the downhill slope, Terry.

Saturday: November 5, 2011

Dicaearchus, that great and prolific Peripatetic, wrote a work called On the Extinction of Human Life. Having assembled the other causes – floods, epidemics, ravages of nature, sudden invasions by hordes of wild beasts, the onset of which he demonstrates has caused the exstirpation of certain races – he then shows how many more men by contrast have been wiped out by attacks made by other men in wars or civil commotions, than by all other disasters.

(Cicero, De Officiis 2.16, tr. P. G. Walsh, Oxford, 2000)

The Latin:

Est Dicaearchi liber de interitu hominum, Peripatetici magni et copiosi, qui collectis ceteris causis eluvionis, pestilentiae, vastitatis, beluarum etiam repentinae multitudinis, quarum impetu docet quaedam hominum genera esse consumpta, deinde comparat, quanto plures deleti sint homines hominum impetu, id est bellis aut seditionibus, quam omni reliqua calamitate.

Wednesday: December 29, 2010

Fans of bluegrass and other traditional American music all know “The Wreck of the Old 97”. Without even trying, I have acquired five versions by four different artists for my iPod: Ernest Stoneman & Kayle Brewer, Hank Thompson, Johnny Cash (live, at San Quentin), and two by Mac Wiseman. For those who do not know the song, it usually begins something like this:

Well they gave him his orders at Monroe, Virginia,

Saying “Steve, you’re way behind time.

This is not 38, it’s old 97.

You must put her into Spencer on time.”

A complete set of lyrics – more complete than in any version I have heard sung – will be found at the Blue Ridge Institute & Museum website. Most singers start with the third verse, quoted above.

Wikipedia’s article on the wreck and the song includes a detail I had not known:

During the late 1940s, a parody of the ballad was sung that mocked the ties that the folk singer Pete Seeger had to the Communist Party.

They give the first four lines, which is enough for Google to find the rest at the Socialist Songbook website:

THE BALLAD OF PETE SEEGER

(Tune: Wreck of the Old ’97)

Well, they gave him his orders

Up at party headquarters,

Saying, “Pete, you’re way behind the times,

This is not ’38; this is 1947,

And there’s been a change in that old party line.”

Well, it’s a long, long haul

From “Greensleeves” to “Freiheit”,

And the distance is more than long,

But that great outfit they call the People’s Artists

Is on hand with those good old People’s songs.

Their motives are pure, their material is corny,

But their spirit will never be broke.

And they go right on in their great noble crusade –

Of teaching folk songs to the folk.

Wikipedia’s Pete Seeger article doesn’t mention the parody.

Sunday: June 27, 2010

Proud Modern Learning despises the antient: School-men are now laught at by School-boys.

(Poor Richard’s Almanack, 1758)

Friday: June 11, 2010

“When people unwittingly eat human flesh, served by unscrupulous restaurant owners and other such people, the similarity to pork is often noted.”

(Galen, On the Power of Foods 3, quoted in J. C. McKeown, A Cabinet of Roman Curiosities, p. 161)

Sunday: May 9, 2010

On a Latin play about Richard III by the master of Caius College, Cambridge (1579):

. . . Legge’s was a poverty-stricken mind; his Latin versification might crimson the cheek of a preparatory schoolboy, and but for the sad fact that by the time they have read sufficiently to write on English literature, scholars have only too often lost the gift, unhappily for their readers, of knowing what is boring and what is not, this fatuous production of a shallow pedant would have been treated with as little respect as it deserves.

(F. L. Lucas, Seneca and Elizabethan Tragedy, 1922, page 97)

He adds a footnote on the last word:

It may be added that John Palmer of St John’s who took the part of Richard “had his head so possest with a prince-like humour” that he behaved like a potentate ever after, and died in prison as a result of his regal prodigalities.

Saturday: March 20, 2010

Ovid was born on March 20th, 43 B.C., and exiled to Tomis (now Constanza, on the coast of Romania) in A.D. 8. There he wrote five books of Tristia and four of Epistulae ex Ponto, lamenting his fate at great and sometimes tedious length. Tristia 3.13 is a gloomy non-celebration of his birthday, and the third book of Tristia can be dated to 10 A.D. (So says Sir Ronald Syme, History in Ovid, 38.) Assuming that it was in fact written on his birthday, anyone who reads it in the next 18 minutes is reading it on the 2000th anniversary of its composition. Anyone in the eastern U.S., that is – it’s already March 21st in Ovid’s hemisphere.

Tuesday: February 9, 2010

Does a 125th birthday count as a significant anniversary? If so — also if not — today is Alban Berg’s 125th. In commemoration, I’m playing the only really tolerable pieces written by the New Vienna School, Berg’s Violin Concerto and Lyric Suite for String Quartet. Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg published a few other pieces that are not just tolerable but very pleasant, but they are arrangements of Strauss waltzes — the Old Vienna School reworked by the New — so they don’t really count.

So what would we call a 125th birthday? A hemi-demi-semi-millennium, of course.

By the way, ‘Alban’ seems an odd name for a German. I mostly know it from the name of the Alban Mount, southeast of Rome. It’s odd that ‘Berg’ is German for mount(ain), though the mountain is apparently not called the Albanberg in German. The ancient Roman name is singular, Albanus Mons, but German Wikipedia gives the plural ‘Albaner Berge’ as the preferred form, with ‘Albaner Hügel’ and ‘Albanergebirge’ as alternatives. I still wonder if Alban’s father was indulging in a pun: perhaps a native speaker can tell us.

Thursday: July 2, 2009

In a recent post at Chicago Boyz, David Foster asks “what the proper Greek would be for ‘government by clowns'”. There are several possibilities:

- A bomolochos was originally “one that waited about the altars, to beg or steal some of the meat offered thereon” (Liddell-Scott), but it acquired a less specific meaning “clown, buffoon”, which was standard in derivatives like the verb bomolocheuomai, “play the buffoon, indulge in ribaldry, play low tricks”, though the idea of begging may be included. So perhaps the best word for “government by clowns” would be bomolocharchy (0 Google hits).

- Since our rulers live at our expense, how about a word that means “one who eats at the table of another, and repays him with flattery and buffoonery”? Compounded with “-archy”, that would give us parasitarchy, whose meaning will be clear even to the Greekless.

- Another possibility would be an animal metaphor for clownishness. The Greek word for ‘ass’ (donkey, not butt) is ónos (plural ónoi), so the shortest word for “rule by clowns, buffoons, asses” would be onarchy.

- The other meaning of English ‘ass’ also provides a very approximate equivalent for ‘clown’, and you don’t need to have studied Greek to figure out what proctarchy would mean.

I’m sure there are other possibilities, but I can’t seem to find my English-Greek Dictionary at the moment.

Sunday: March 15, 2009

A boy, an ungrown child, in seven years puts forth

a line of teeth and loses them again;

but when another seven God has made complete,

the first signs of maturity appear.

In the third hebdomad he’s growing yet, his chin

is fuzzy, and his skin is changing hue,

while in the fourth one, each achieves his peak of strength,

the thing that settles whether men are men.

The fifth is time a man should think of being wed

and look for sons to carry on his line;

and by the sixth he’s altogether sensible,

no more disposed to acts of fecklessness.

With seven hebdomads and eight — fourteen more years —

wisdom and eloquence are at their peak,

while in the ninth, though he’s still capable, his tongue

and expertise have lost some of their force.

Should he complete the tenth and reach the measured line,

not before time he’d have his due of death.

(Solon, Fr. 27, tr. M. L. West)

Monday: March 2, 2009

Mickey Kaus titles a post on card check ‘Et Tu, Baucus’. Modern names with Latinate endings are rare, and I’m disappointed that he didn’t make it Et Tu, Bauce: that would be the appropriate vocative singular form of Baucus if it were a Latin name. I suppose that would have confused too many of his readers in this Latinless age.

Tuesday: February 3, 2009

In his commentary on Horace’s Soracte Ode (1.9), David West writes:

“Horace says sententiously, ‘When winds stop blowing, trees stop shaking’, meaning of course that unpleasant things do not last for ever. This could be said of a plague of locusts or a broken ankle or a professor with tenure” (Horace Odes I: Carpe Diem, Oxford 1995, 42-3)

The third unpleasant thing is odd at first glance, and suggests that West had at least one unpleasant colleague to put up with until he either died or retired.

Tuesday: November 11, 2008

I’m not sure why my comments aren’t working, and why I can’t even use FTP. Until I can fix that, readers may contact me by e-mail at the following address, after carefully reversing it: gro.liveewrd@liveewrd.

Friday: November 16, 2007

A sure sign of a good book is that the older we grow the more we like it. A youth of 18 who wanted and above all could say what he felt would say of Tacitus something like the following: Tacitus is a difficult writer who knows how to depict character: and sometimes gives excellent descriptions, but he affects obscurity and often introduces into the narration of events remarks that are not very illuminating; you have to know a lot of Latin to understand him. At 25 perhaps, assuming he has in the interim done more than read, he will say: Tacitus is not the obscure writer I once took him for, but I have discovered that Latin is not the only thing you need to know to understand him — you have to bring a great deal with you yourself. And at 40, when he has come to know the world, he may perhaps say: Tacitus is one of the greatest writers who ever lived.

(Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, Aphorisms, translated by R. J. Hollingdale, E 43)

Lichtenberg was still in his early thirties when he wrote this. I take it that the 18-year-old cannot always say what he thinks because he is still in school.

Here is the German for those who can handle it:

Ein sicheres Zeichen von einem guten Buch ist, wenn es einem immer besser gefällt je älter man wird. Ein junger Mensch von 18, der sagen wollte, sagen dürfte und vornehmlich sagen könnte was er empfindet, wüde von Tacitus etwa folgendes Urteil fällen: Tacitus ist ein schwerer Schriftsteller, der gute Charaktere zeichnet und vortrefflich zuweilen malt, allein er affektiert Dunkelheit und kommt oft mit Anmerkungen in die Erzählung der Begebenheiten herein, die nicht viel erläutern, man muß viel Latein wissen um ihn zu verstehn. Im 25ten vielleicht, vorausgesetzt, daß er mehr getan hat als gelesen, wird er sagen: Tacitus ist der dunkle Schriftsteller nicht für den ich ihn ehmals gehalten, ich finde aber, daß Latein nicht das einzige ist was man wissen muß um ihn zu verstehen, man muß sehr viel selbst mitbringen. Und im 40ten, wenn er die Welt hat kennen lernen, wird er vielleicht sagen, Tacitus ist einer der ersten Schriftsteller, die je gelebt haben.

(Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, Sudelbücher, E 197 — 2nd half)

Sunday: October 21, 2007

Facts about the ancient world, even when mentioned in ancient texts, are not always found in the texts we would think of consulting first, or second, or at all. In his commentary on Martial I, Peter Howell refers (205) to Philodemus, On Methods of Inference (II.3f., if anyone wants to look it up) as the source for a list of “celebrated dwarfs (Egyptian, and possibly Syrian)”. What dwarfs and their names have to do with formal logic is not obvious, though I’m not quite intrigued enough to try to find out.

Tuesday: July 24, 2007

InstaPundit links to a story from the Knoxville News about Tina, a Shire breed horse claimed to be the world’s tallest. The dubious historical claim is half a sentence: “Shires date to the Trojan War . . . .” What possible evidence could support that claim?

Sunday: June 17, 2007

What one British rogue learned at school in the early 19th century:

. . . I was sent to one of the most fashionable and famous of the great public schools. I will not mention it by name, because I don’t think the masters would be proud of my connection with it. I ran away three times, and was flogged three times. I made four aristocratic connections, and had four pitched battles with them; three thrashed me, and one I thrashed. I learned to play at cricket, to hate rich people, to cure warts, to write Latin verses, to swim, to recite speeches, to cook kidneys on toast, to draw caricatures of the masters, to construe Greek plays, to black boots, and to receive kicks and serious advice resignedly. Who will say that the fashionable public school was of no use to me after that?

(Wilkie Collins, A Rogue’s Life, Chapter I)

Comments Off on The Value of a First-Class Education

Tuesday: April 10, 2007

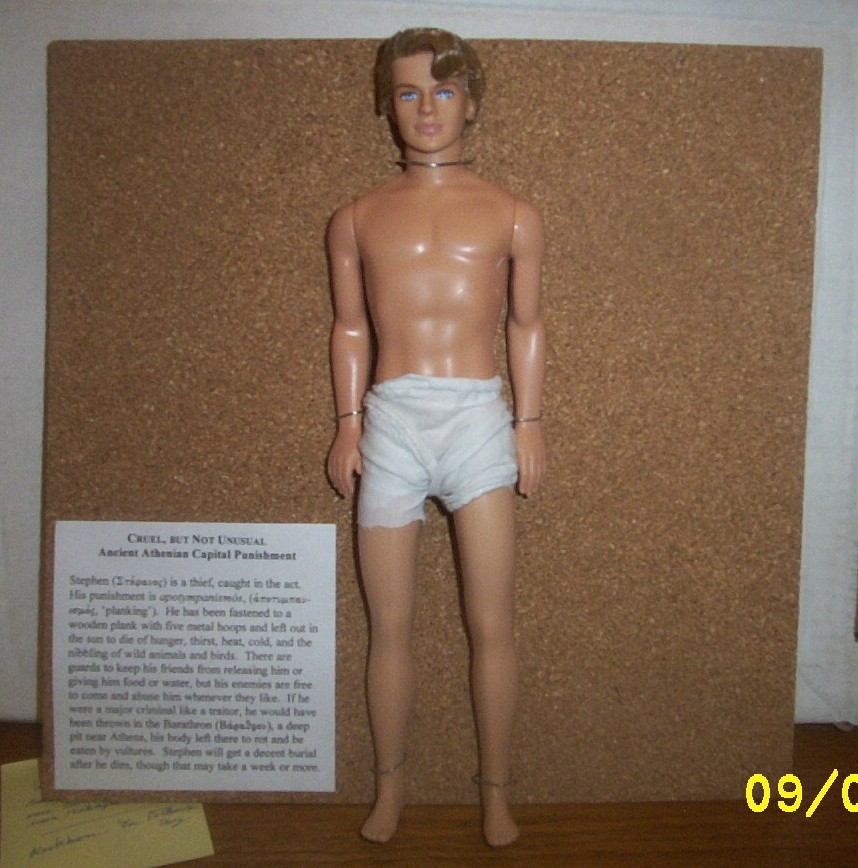

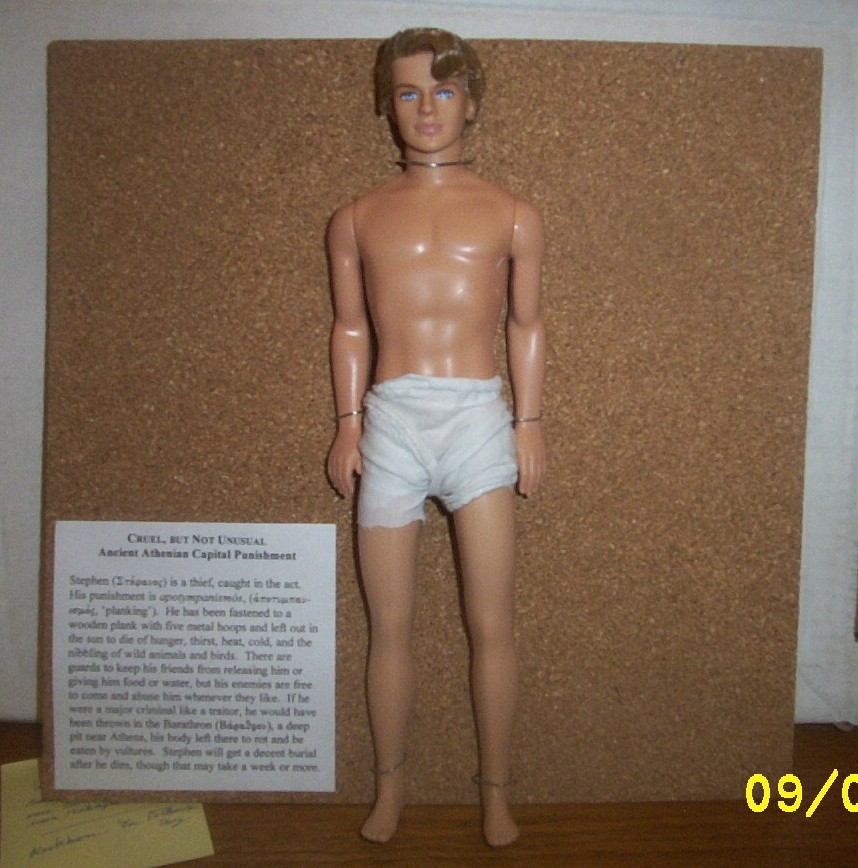

Many of my students — especially a couple of 7th-grade boys — show a great deal of interest in ancient forms of capital punishment. Today I put together a model to illustrate the Athenian practice of apotumpanismós, or ‘planking’, which is essentially crucifixion without the nails (paradoxically, that makes it crueler):

The text on the lower left reads:

CRUEL, BUT NOT UNUSUAL

Ancient Athenian Capital Punishment

Stephen (Stéphanos) is a thief, caught in the act. His punishment is apotympanismós (‘planking’). He has been fastened to a wooden plank with five metal hoops and left out in the sun to die of hunger, thirst, heat, cold, and the nibbling of wild animals and birds. There are guards to keep his friends from releasing him or giving him food or water, but his enemies are free to come and abuse him whenever they like. If he were a major criminal like a traitor, he would have been thrown in the Bárathron, a deep pit near Athens, his body left there to rot and be eaten by vultures. Stephen will get a decent burial after he dies, though that may take a week or more.

That’ll teach Stephen to steal Barbie’s purse. It’s too bad about the hair-style — and the silly happy look on his face.

Next project: the Bárathron. That will take a bit more money, but will be easy enough. Take one large-sized plastic garbage can, add a small shelf on one side at the top, line the interior and the shelf with papier-maché to represent bare rock, add a fully-clothed Ken and Barbie throwing a loin-cloth’d Stephen over the edge, and put the pieces of another Stephen down in the bottom, with the broken-up remains of a couple of plastic skeletons, if I can find them in the right size. Bushes and vultures are optional, though they would add a bit of atmosphere. I’ll probably enlist my students to work on that, since their experience with papier-maché is undoubtedly fresher than my own (by 40 years or so, I estimate).

Comments Off on Cruel, But Not Unusual

Monday: March 19, 2007

Next Tuesday, the Criterion Collection will be coming out with a five-DVD collection of Ingmar Bergman’s earliest movies. Here’s the IMDB plot summary of the earliest of all, Hets or Torment (1944):

Jan-Erik Widgren is a high-school senior. His Latin teacher, Caligula, is feared by everybody, both teachers and students. Widgren falls in love with Berta, who works in a tobacco store. She tells him that she is harassed by a mean, sadistic man, but does not tell him that it is Caligula himself.

Here’s a user comment:

The brilliance of Stig Järrel needs to be mentioned. He is so convincing in his performance that when you’re leaving the movie-theater you might just see him coming around the corner with his wooden ruler . . .

According to IMDB, this was a reprise of a previous performance as a sadistic Latin teacher in a non-Bergman movie, not available on DVD. I hope my local Border’s has the Bergman set in stock on the day of release, since that’s also the last day of Teacher Appreciation Weekend (March 22-27).

Comments Off on A Must-Have For Latinists?

Sunday: February 18, 2007

La lectura matutina de Homero, con la serenidad, el sosiego, la honda sensación de bienestar moral y físico, de salud perfecta, que nos infunde, es el mejor viático para soportar las vulgaridades del díia.

The reading of Homer every morning, with the serenity, the tranquillity, the deep sensation of moral and physical well-being which it instills in us, is the best provision to endure the vulgarities of the day.

(Nicolás Gómez Dávila, Notas, 210)

Comments Off on Aphorism Of The Day

|

|